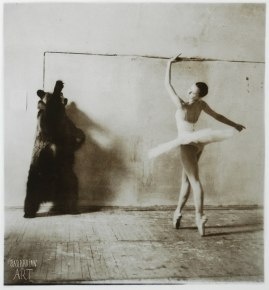

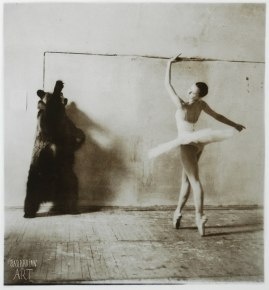

In late winter I sometimes glimpse bits of steam coming up from some fault in the old snow and bend close and see it is lung-colored and put down my nose and know the chilly, enduring odor of bear.

The Bear

Galway Kinnell

Galway Kinnell (born February 1, 1927) is an American poet. For his 1982 Selected Poems he won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and split the National Book Award for Poetry with Charles Wright. From 1989 to 1993 he was poet laureate for the state of Vermont. An admitted follower of Walt Whitman, Kinnell rejects the idea of seeking fulfillment by escaping into the imaginary world. His best-loved and most anthologized poems are “St. Francis and the Sow” and “After Making Love We Hear Footsteps”