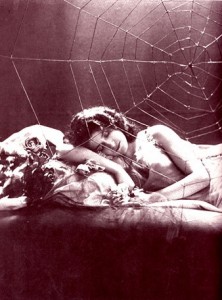

Arachnia weaves and she weaves so well

She weaves a passage where the Gods will fly

Athena laughs as she casts her spell

While she watches from her loom on high

Arachni, Arachnia

The Goddess Athena’s got a quest for you

And you must weave a story of the Gods that rule

In all their mystery and you must tell it true

So Arachnia’s woven the seven moons

She’s spun the silver thread upon an applewood loom

And she’s told the story of the Gods that rule

In all their mystery and yeah she’s told it true

Spiral Dance

Perhaps one of the most ancient and widely distributed traditions in the western Indo European lore is that of the Three Sisters of Destiny; known to the Northern tribes as the Norns. Each of the sisters represent a different aspect of time: the first, an old hag, peers off into the left or west… Urdr, the past. The second, a woman of middle-years, stares straight ahead to the south… Verdandi, the present. And the third, a youth, looks off to the right or east… Skuld, the future.

Skuld (the name possibly means “debt” or “future”) is a Norn in Norse mythology. Skuld makes up a trio of Norns that are described as deciding the fates of people. In the Prose Edda book Gylfaginning, Snorri informs the reader that Skuld is the youngest of the Norns, and that she is also a valkyrie, taking part in the selection of warriors from the slain. “…and the youngest Norn, she who is called Skuld, ride ever to take the slain and decide fights”. Skuld often bends the threads of destiny already spun by Urd and Verdande, and Skuld is also the Norn who decides the length of the life thread.

The Norns in Norse mythology are female beings who rule the destiny of gods and men, a kind of dísir comparable to the Fates in Greek mythology. According to Snorre Sturlason’s interpretation of the Völuspá, the three most important norns, Urd (past), Verdande (present) and Skuld (future) come out from a hall standing at the Well of Urðr ( the Well of fate) and they draw water from the well and take sand that lies around it, which they pour over Yggdrasil so that its branches will not rot. These norns are described as three powerful maiden giantesses (Jotuns) whose arrival from Jötunheimr ended the golden age of the gods. Beside these three norns, there are many other norns who arrive when a person is born in order to determine his or her future.

The Norns in Norse mythology are female beings who rule the destiny of gods and men, a kind of dísir comparable to the Fates in Greek mythology. According to Snorre Sturlason’s interpretation of the Völuspá, the three most important norns, Urd (past), Verdande (present) and Skuld (future) come out from a hall standing at the Well of Urðr ( the Well of fate) and they draw water from the well and take sand that lies around it, which they pour over Yggdrasil so that its branches will not rot. These norns are described as three powerful maiden giantesses (Jotuns) whose arrival from Jötunheimr ended the golden age of the gods. Beside these three norns, there are many other norns who arrive when a person is born in order to determine his or her future.There were both malevolent and benevolent norns, and the former caused all the malevolent and tragic events in the world while the latter were kind and protective goddesses. Recent research has discussed the relation between the myths associated with norns and valkyries and the actual travelling Völvas (seiðr-workers), women who visited newborn children in the pre-Christian Norse societies.

The theme of weaving in mythology is ancient, and its lost mythic lore probably accompanied the early spread of this art. In traditional societies today, westward of Central Asia and the Iranian plateau, weaving is a mystery within woman’s sphere. Where men have become the primary weavers in this part of the world, it is possible that they have usurped the archaic role among the gods, only goddesses are weavers. Herodotus noted, however, the cultural difference between gender identities and weaving among Hellenes and Egyptians: among Egyptians it was the men who wove. Weaving begins with spinning. Until the spinning wheel was invented in the 14th century, all spinning was done with distaff and spindle.

In English the “distaff side” indicates relatives through one’s mother, and thereby denotes a woman’s role in the household economy. In Scandinavia, the stars of Orion’s belt are known as Friggjar rockr, “Frigg’s distaff”. In pre-Dynastic Egypt, nt (Neith, Nuit, Nut) was already the goddess of weaving (and a mighty aid in war as well). She protected the Red Crown of Lower Egypt before the two kingdoms were merged, and in Dynastic times she was known as the most ancient one, to whom the other gods went for wisdom. Nit is identifiable by her emblems: most often it is the loom’s shuttle, with its two recognizable hooks at each end, upon her head.

In Greece the Moirai (the “Fates”) are the three crones who control destiny, and the matter of it is the art of spinning the thread of life on the distaff. Ariadne, the wife of the god Dionysus in Minoan Crete, possessed the spun thread that led Theseus to the center of the labyrinth and safely out again. Among the Olympians, the weaver goddess is Athena, who punished the impious pretensions of her acolyte Arachne by turning her into a weaving spider. For the Norse peoples, Frigg is a goddess associated with weaving.

The Scandinavian “Song of the Spear”, quoted in “Njals Saga”, gives a detailed description of Valkyries as women weaving on a loom, with severed heads for weights, arrows for shuttles, and human gut for the warp, singing an exultant song of carnage.

In Germanic mythology, Holda (Frau Holle) and Perchta (Frau Perchta, Berchta, Bertha) were both known as goddesses who oversaw spinning and weaving. They had many names. In Celtic mythology The goddess Brigantia, due to her identification with the Roman Minerva, may have also been considered, along with her other traits, to be a weaving deity.

In Baltic myth, Saule is the life-affirming sun goddess, whose numinous presence is signed by a wheel or a rosette. She spins the sunbeams. The Baltic connection between the sun and spinning is as old as spindles of the sun-stone, amber, that have been uncovered in burial mounds. Baltic legends as told have absorbed many images from Christianity and Greek myth that are not easy to disentangle.

In Inca mythology, Mama Ocllo first taught women the art of spinning thread. In Tang Dynasty China, the goddess weaver floated down on a shaft of moonlight with her two attendants. She showed the upright court official Guo Han in his garden that a goddess’s robe is seamless, for it is woven without the use of needle and thread, entirely on the loom. The phrase “a goddess’s robe is seamless” passed into an idiom to express perfect workmanship. This idiom is also used to mean a perfect, comprehensive plan. The Goddess Weaver, daughter of the Celestial Queen Mother and Jade Emperor, wove the stars and their light, known as “the Silver River” (what Westerners call “The Milky Way Galaxy”), for heaven and earth. She was identified with the star Westerners know as Vega.

The Finnish epic, the Kalevala, has many references to spinning and weaving goddesses. In later European folklore, weaving retained its connection with magic. Mother Goose, traditional teller of fairy tales, is often associated with spinning. She was known as “Goose-Footed Bertha” or Reine Pédauque (“Goose-footed Queen”) in French legends as spinning incredible tales that enraptured children. The daughter who, her father claimed, could spin straw into gold and was forced to demonstrate her talent, aided by the dangerous earth-daemon Rumpelstiltskin was an old tale when the Brothers Grimm collected it. Similarly, the unwilling spinner of the tale The Three Spinners is aided by three mysterious old women. In The Six Swans, the heroine spins and weaves starwort in order to free her brothers from a shapeshifting curse. Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle are enchanted and bring the prince to marry the poor heroine. Sleeping Beauty, in all her forms, pricks her finger on a spindle, and the curse falls on her.

In Alfred Tennyson’s poem “The Lady of Shalott”, her woven representations of the world have protected and entrapped Elaine of Astolat, whose first encounter with reality outside proves mortal. William Holman Hunt’s painting from the poem contrasts the completely pattern-woven interior with the sunlit world reflected in the roundel mirror. On the wall, woven representations of Myth (“Hesperides”) and Religion (“Prayer”) echo the mirror’s open roundel; the tense and conflicted Lady of Shalott stands imprisoned within the brass roundel of her loom, while outside the passing knight sings “‘Tirra lirra’ by the river” as in Tennyson’s poem.