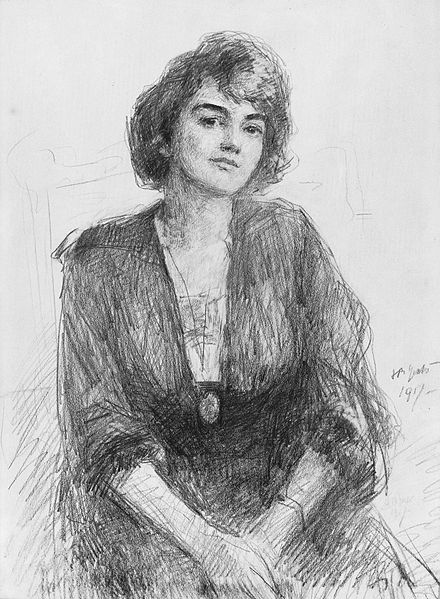

Jeanne Robert Foster (1879 – 1970)

Jeanne Robert Foster was an American poet from the Adirondack Mountains. She was born Julia Elizabeth Oliver in Johnsburg, New York.

In 1896 she married Matlock Foster, and lived in Rochester, New York. She studied drama at the Stanhope-Wheatcroft Dramatic School, and worked in magazine journalism. She became a leading fashion model. The couple then moved to Boston; she continued to work as a journalist there and in New York, becoming literary editor of the American Review of Reviews.

In 1916 she began to publish narrative verse about the Adirondacks. From this period she travelled in Europe, met important figures of modernism, and co-operated with the collector John Quinn in building up his contemporary art collection. After Quinn’s death in 1924 Jeanne helped prepare the collection of his letters that became the John Quinn Memorial Collection at the New York Public Library. The collection includes an extensive correspondence with Joseph Conrad.

In 1932 she moved to Schenectady, where she worked as a social worker.

Jeanne’s friends included many of the period’s leading authors and artists. She was particularly close to Ford Madox Ford, Ezra Pound, and William Butler Yeats.

On June 10, 1915, Aleister Crowley met Jeanne in the company of her friend Hellen Westley; Jeanne was thirty-six when they met. Crowley would have affairs with both women, dubbing them with the theriomorphic names of The Cat and The Snake, drawn from the Egyptian gods Pasht and Apophis.

It was love at first sight. Crowley asked if she might critique his recent writings and help him improve his prose. Jeanne suggested they meet for tea at her club the next afternoon. By the end of tea time, Crowley felt he knew her intimately. Bidding her farewell Crowley said “So, you are tied to this old satyr who snatched you from the cradle. And where does that leave me?” “I loved you at first sight” she replied, “As a spiritual brother.” Then she kissed him and tea ended.

Jeanne was one of Crowley’s great loves. Crowley wrote that “I saw my ideal incarnate… I really loved her with a love more exalted than aught in all my experience.” She kept him waiting a month before consummating the liaison, probably something of a record for Crowley, who wrote in his Confessions; “I endured the torture of absence, of doubt, of despair, with all the might of my manhood.” It was indeed a serious relationship; they wrote love poetry to one another, and she considered divorcing her husband to marry Crowley. Crowley’s plan was to have a his first male offspring with Jeanne. Jeanne assumed the office of Scarlet Woman in his magical workings, choosing Hilarion as her mystic name. In late September Crowley tried to beget a child by her and – as evidenced in the final poems of The Golden Rose (the unpublished sonnet cycle chronicling their affair) – he believed he had succeeded, but, she did not get pregnant.

(The Golden Rose was written under the inspiration of Jeanne Robert Foster, Hilarion. Their life together was moderately turbulent but mercifully brief! Actually, Jeanne seemed to come out of the whole experience rather well. And she lived on until 1970, when she died at the age of ninety-one.)

In early October Crowley set out for a tour of the West Coast, followed by Jeanne, who had decided to spice the romance and adventure by taking her husband in tow. They took a side trip to Vancouver, where Crowley visited Charles Stansfeld Jones, a member of the A.*.A.*. and the Ordo Templi Orientis.

They parted in California; on Crowley’s return to New York he learned that she had dropped him. He felt the loss acutely. He had been certain she had conceived his child, later writing that “I did not know that I was attempting a physical impossibility.” Crowley regained his emotional equilibrium, dismissing the affair as an illusion, and Jeanne Foster as deceitful. Five years later he wrote: “I have not been in love since 1915… Did she really ‘break my heart’?”

O bitter herb, Forgetfulness,

I search for you in vain;

You are the only growing thing

Can take away my pain.

When I was young, this bitter herb

Grew wild on every hill;

I should have plucked a store of it,

And kept it by me still.

I hunt through all the meadows

Where once I wandered free,

But the rare herb, Forgetfulness,

It hides away from me.

O bitter herb, Forgetfulness,

Where is your drowsy breath?

Oh, can it be your seed has blown

Far as the Vales of Death?

Jeanne Robert Foster

__________________________________________________

Jeanne Foster was always concerned with being a lady, even through a career that linked her intimately with some of the most influential men of her time. She maintained until the last the pose of the proper matron, although her diaries reveal quite another story. This reticence, which imbues much of her other poetry, is not to be found in Neighbors of Yesterday. There she speaks boldly and directly. The ruin of Silence Davis by her clod of a husband is dealt with straightforwardly, as is the near frozen lunacy of the woman with the green bow, who interrupts her ceaseless sweeping at the poor farm to attach a threadbare bow to her dress. She cannot bear the thought that any visitor should see her without her badge of respectability. As Foster says in “Alec Hill: The Good-For-Nothing,” “Respectability’s half in its trappings.”

In “Her Flowers,” there is an explosion of color in a woman’s garden which challenges the austerity of the Adirondacks. We learn that the old woman, who died because she was reluctant to allow the doctor to see her breast, made her garden of cuttings from the graves in her small community, and identified each flower with the deceased: “This bush is Niece Abigal’s snowdrop, / And that vine is Uncle John’s myrtle.” In this way the annals of the community are kept. Women, the glue of the society, insure its continuation by transferring the blooms from graves to their country gardens, keeping vital the “green fuse” that unites us all.

Although she did not enjoy the fame of Nobel Prize winner Yeats or the extraordinary glory of writer Ernest Hemingway, her regional pervasiveness and precise talent make her a local hero.

signed c.r.: J.B. Yeats / 1917

Jeanne Robert Foster is buried near her friend John Butler Yeats, the painter and father of William Butler Yeats, in the Chestertown Rural Cemetery in the Adirondacks. Her own papers can be found in the Jeanne R. Foster-William M. Murphy Collection at the New York Public Library and at Harvard University’s Houghton Library, which holds her correspondence with poet and author Ezra Pound.

Jeanne Robert Foster’s Works:

Neighbors of Yesterday (1916)

Wild Apples (1916)

External links:

Jeanne Robert Foster (Wikipedia)